A review of ‘A new kind of Christianity’ by Brian McLaren

By Dr Christopher Peppler

Brian McLaren is an influential Post Modern thinker in Christian circles. For that reason alone, his latest book A New Kind of Christianity, deserves probing and analysis for its impact on biblical truth and the centrality of Jesus to his arguments.

Brian McLaren has recently published his most definitive work to date in which he comes closer than ever before to clearly stating what he believes. The book is subtitled, ‘Ten questions that are transforming the faith’ and the book is structured around two sets of five of these questions. He doesn’t state that the design is intended to contrast with the Ten Commandments, but the connection seems obvious – ten commandments on two tablets versus ten questions in two ‘books’. Brian states that the first book contains the ‘profound and critical questions that are being raised by followers of Christ around the world.’ (Pg. xi). The second set of five are, according to Brian, ‘less profound or theologically radical’ (Pg. xi) and are more practical in nature. I will deal with each of the ten questions, but first a couple of general comments.

Firstly, most of the questions are valid topics of interest. Today’s generation might well be asking them in their own way, yet they are questions every generation has posed in some form or other. However, there is presumption in the subtitle - I don’t think that the answers given, or the way the quest is being conducted, is in fact transforming the church. The vast majority of church theologians and leaders alive today have asked these questions but their answers have yielded, in the main, what we refer to as evangelical orthodoxy and not a new kind of Christianity.

Secondly, Brian contends that most people view the Bible, and God’s overarching plan, through one particular pair of theological spectacles. I don’t think that this is true on the scale he proposes. In any event, we all, including Brian, look through one or other set of ‘spectacles’. He also claims that most people read backwards from the church theologians back to the scriptures, and again I think that this is a wrong assumption. His contention is that we are seeing the Bible through the eyes of others and not through the illumination given by the Spirit. This underlying dichotomy sets up an unhelpful tension. As a critic, I am automatically positioned as one who is reading through out-dated and distorting spectacles. This makes it hard to interact with Brian’s observations without being written off as theologically myopic. Notwithstanding, I will attempt as fair a response as I can to Brian’s ten contentions.

Question One: What is the overarching storyline of the Bible?

Brian’s answer to this question influences his responses to all the other questions. He contends that the majority of today’s Christians have bought into a story line that has been imposed upon the scripture and that is in fact alien to it. He calls this aberration the Greco-Roman narrative, a product, so he says, of Plato’s and the Roman Empire’s philosophy. He makes no real attempt to support his contentions from either history or the writings of the early Greek philosopher. Briefly, this narrative reads as follows: God created man, man sinned and fell, God saves a few, and the rest are doomed to an eternity of conscious torment. Understandably, he writes, ‘How in the world, how in God’s name, could anyone everthink this is the narrative of the Bible?’ (Pg. 48)Well I, and all the theologians I know, don’t think that this is the Meta Narrative of the Bible, and so any attempt by Brian to invalidate this narrative is, for me, simply a straw-man argument.

Brian’s answer to this question influences his responses to all the other questions. He contends that the majority of today’s Christians have bought into a story line that has been imposed upon the scripture and that is in fact alien to it. He calls this aberration the Greco-Roman narrative, a product, so he says, of Plato’s and the Roman Empire’s philosophy. He makes no real attempt to support his contentions from either history or the writings of the early Greek philosopher. Briefly, this narrative reads as follows: God created man, man sinned and fell, God saves a few, and the rest are doomed to an eternity of conscious torment. Understandably, he writes, ‘How in the world, how in God’s name, could anyone everthink this is the narrative of the Bible?’ (Pg. 48)Well I, and all the theologians I know, don’t think that this is the Meta Narrative of the Bible, and so any attempt by Brian to invalidate this narrative is, for me, simply a straw-man argument.

Brian answers his lamenting question by proposing that we have bought into this false narrative because we read it backwards from modern theologians, through reformation theologians, then church Fathers and finally back to Jesus. By the time we get back to source we are already wearing distorting spectacles. I just don’t think this is true. Countless modern theologians have sought as best they can to look at the scriptures with fresh eyes and only then to validate their observations against historic church formulations. However, Brian believes that the Greco-Roman mind-set we bring to the reading of scripture is so strong and invasive that we fail to encounter the Elohim God of Abraham or Jesus, but instead find a Zeus-like projection whom Brian calls Theos. He is essentially saying that most readers have a Gnostic understanding of the Bible. He writes, ‘Every time we use terms like the fall and original sin, I believe, many of us are unknowingly importing more or less of this package of Greco-Roman, non-Jewish and therefore non-biblical concepts, like smugglers bringing foreign currency into the biblical economy, or tourists introducing invasive species into the biblical ecosystem.’ (Pgs. 57-58)

Actually, Brian does not believe in the fall or original sin. According to him, instead of documenting the rebellious fall of man, the early chapters of Genesis present ‘a kind of compassionate coming-of-age story.’ (Pg. 64) Brian reinterprets the Garden of Eden narrative. According to him, God simply states that if they eat of the forbidden fruit then, on that same day, they will die – ‘not spiritually die, not relationally die, not ontologically die, but simply die.’ (Pg. 65)

Actually, Brian does not believe in the fall or original sin. According to him, instead of documenting the rebellious fall of man, the early chapters of Genesis present ‘a kind of compassionate coming-of-age story.’ (Pg. 64) Brian reinterprets the Garden of Eden narrative. According to him, God simply states that if they eat of the forbidden fruit then, on that same day, they will die – ‘not spiritually die, not relationally die, not ontologically die, but simply die.’ (Pg. 65)

Adam and Eve did not drop down dead on that day. So in what sense did they die? Well, according to Brian, God changed His mind and instead of killing them, He made clothes for them. Thus starts, what Brian describes, as ‘the first stage of ascent as human beings progress from the life of hunter-gatherers to the life of agriculturalists and beyond.’ (Pg. 66) He then completes the process of making a silk purse from a sows ear by observing that man’s disobedience to God’s primal injunction ‘results in obedience to a former command which never could have been obeyed from within the garden (be fruitful, multiply, fill and subdue the earth)’. (Pg. 67)

All of this seems farfetched to anyone with an orthodox theological training but, according to the thesis Brian presents, this would be due to the alien Greco-Roman Narrative mind-set. Of course, I have many questions that spring to mind. Questions like, was God lying when He told Adam and Eve that they would die the day they ate the forbidden fruit? Was the serpent a saviour figure when it encouraged Eve to disobey God? What sort of a game was God playing anyway when He told them not to eat the fruit while really wanting them to so that He could expel them and thus allow them to ascend?

Another huge question I have, is what then do we do with the contradictory scriptural evidence in places such as Romans 5:12-19? What did Paul mean when he wrote, ‘Therefore, just as sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all men, because all sinned’? And what did he have in mind when he penned, ‘For if the many died by the trespass of the one man, how much more did God's grace and the gift that came by the grace of the one man, Jesus Christ, overflow to the many! Again, the gift of God is not like the result of the one man's sin: The judgment followed one sin and brought condemnation, but the gift followed many trespasses and brought justification. For if, by the trespass of the one man, death reigned through that one man, how much more will those who receive God's abundant provision of grace and of the gift of righteousness reign in life through the one man, Jesus Christ. Consequently, just as the result of one trespass was condemnation for all men, so also the result of one act of righteousness was justification that brings life for all men. For just as through the disobedience of the one man the many were made sinners, so also through the obedience of the one man the many will be made righteous.’?

Brian of course has a reinterpretation of the whole book of Romans and I will mention that further on in this review. What this convoluted tale of ascent through disobedience reveals most clearly is the liberal hermeneutical system Brian employs. Orthodox evangelical hermeneutics allows for different literary forms within the biblical revelation, yet respects the text enough to refrain from bending it to fit a human philosophy or reading into it what it does not say. The Genesis account does not suggest, even by inference, that God was lying to Adam and Eve (that would cause a whole lot of theological problems of its own) and nor does it infer that God changed His mind about the death penalty.

Brian of course has a reinterpretation of the whole book of Romans and I will mention that further on in this review. What this convoluted tale of ascent through disobedience reveals most clearly is the liberal hermeneutical system Brian employs. Orthodox evangelical hermeneutics allows for different literary forms within the biblical revelation, yet respects the text enough to refrain from bending it to fit a human philosophy or reading into it what it does not say. The Genesis account does not suggest, even by inference, that God was lying to Adam and Eve (that would cause a whole lot of theological problems of its own) and nor does it infer that God changed His mind about the death penalty.

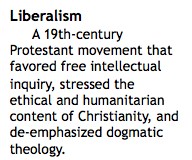

Liberalism denies the supernatural and so if Adam did not drop down dead when he and Eve ate the fruit then it can only mean that either God was bluffing or He changed his mind. Real and actual spiritual death just doesn’t fit into the liberal paradigm. Brian gives some support to my suspicion when he later attributes the Egyptian plagues as natural phenomena. He writes, ‘The so-called supernatural, in this way, seems remarkably natural.’ (Pg. 77)

Even in these early chapters of the book, it starts to become clear that whilst Brian contends that most others read through Greco-Roman spectacles, he himself is reading the biblical narrative through Liberal spectacles. And with that in mind, we need to progress to the second of the ten responses that are distorting the faith.

See also http://www.rpmministries.org/2010/03/responding-to-brian-mclarens-question-1-the-narrative-question/

Liberalism denies the supernatural and so if Adam did not drop down dead when he and Eve ate the fruit then it can only mean that either God was bluffing or He changed his mind. Real and actual spiritual death just doesn’t fit into the liberal paradigm. Brian gives some support to my suspicion when he later attributes the Egyptian plagues as natural phenomena. He writes, ‘The so-called supernatural, in this way, seems remarkably natural.’ (Pg. 77)

Even in these early chapters of the book, it starts to become clear that whilst Brian contends that most others read through Greco-Roman spectacles, he himself is reading the biblical narrative through Liberal spectacles. And with that in mind, we need to progress to the second of the ten responses that are distorting the faith.

See also http://www.rpmministries.org/2010/03/responding-to-brian-mclarens-question-1-the-narrative-question/

Question Two: How should the Bible be understood?

Brian starts his discussion with a prolonged critique of how his predecessors supported the practice of slavery by quoting the Bible. He also slips in the matter of South African apartheid for good measure. He claims that these ungodly interpretations of scripture came about because of the ‘habitual, conventional way of reading and interpreting the Bible.’ (Pg. 100) All of this is to prepare the ground for the major contention that ‘our quest for a new kind of Christianity requires a new, more mature and responsible approach to the Bible.’ (Pg. 101) Obviously, we will need this sort of perspective if we are to accept his strange reformulation of the Genesis account of sin and separation from God. What then is this ‘more mature’ way of reading and understanding the scriptures?

Brian contends that most evangelicals read the Bible as though it were a constitution. By this, he means that we tend to read the Bible as though it were merely a set of rules and laws and inflexible propositions. He writes, ‘We seek to distinguish ’spirit’ from ‘letter’ and argue the ‘framers’ intent’, seldom questioning whether the passage under review was actually intended by the original authors and editors to be a universal, eternally binding law.’ (Pg. 103) This of course is patently incorrect. One of the basic principles of evangelical biblical interpretation is to seek to answer the question ‘what did the original hearers or readers understand by this?’ In seeking to answer this question, we take into consideration the biblical, historical, and cultural contexts. We also seek to make critical determinations between specific history-bound incidents and universal principles. But having set up this straw man argument Brian then proceeds to claim that ‘read as a constitution, the Bible has passages that can and have been used to justify, if not just about anything, an awful lot of wildly different things.’ (Pg. 103) This last part is true, but not because of a so-called constitutional approach to scripture, but because of bad hermeneutics!

But, if the ‘constitutional’ view is immature and harmful, then what is the mature and productive view of the Bible? Brian’s answer is that we need to understand the Bible as a portable library. Of course, the Bible is a library of sixty-six books. But whose library is it? ‘It’s the library of a culture and community.’ (Pg. 105) Which culture and community is this? It is the Jewish culture, then the early church community, then in a sense, the current Christian community. This is an important point. What he is essentially suggesting is that the Bible is the product of a particular people within a historic period who sought to document their understanding of God, mankind, history, and so on. We, as the current believing community should reframe its observations in terms of our current culture and times. It is not that Brian regards the Bible as uninspired for he writes that ‘I certainly believe that in a unique and powerful way God breathes life into the Bible.’ (Pg. 108) He also accepts that the biblical library is uniquely important to us as modern followers of Christ Jesus, but as a community resource and not as an authoritative ‘constitution’.

It is hard to pin down exactly what he means at this point but it seems that Brian has a distinctly non-orthodox understanding of biblical inspiration and authority. He appears to suggest that biblical authority rests in a community’s understanding of the progressive, evolutionary, understanding of God and His ways. To illustrate his view of this he evaluates the book of Job. He claims that at the end of the book God appears to be contradicting the truth of everything that Job’s comforters have said. He then asks how we can then claim that the bulk of the book of Job is inspired in the traditional sense. He also suggests that ‘God’ in Job is a character and that the book does not set out to record what God actually did say to Job. Its value to us lies in the drama it presents which enables us to enter into dialogue with the real God as we read and ponder on the contents of the book. To use his words, ‘to say that the text is inspired is to say that people can encounter God – the real God – in a story full of characters named Job, Eliphaz, Bildad, Satan, and even one called God’ (Pg. 123)

Brian claims that his approach to the Bible is neither conservative nor liberal but a third way that puts us neither under nor above the text, but ‘in the text- in the conversation, in the story.’ (Pg. 125) However, I am hard-pressed to see how his approach is anything other than liberal.

Brian’s responses to these two first questions are foundational to his entire theology. Actually, the second question conditions the first. If we understand the Bible to be a cultural collection of stories that we receive, not as statements of truth, but as invitations to enter into community discourse within the people of faith, then we can reinterpret the overarching narrative of scripture any way we want.

See also http://www.rpmministries.org/2010/03/responding-to-brian-mclaren%E2%80%99s-question-2-the-authority-question/

Question Three: Is God violent?

The main point that Brian makes here is that the Bible reflects an evolving human understanding of God’s nature and character. He contends that the many violent stories in the Old Testament are descriptions of how the people of that day saw God as a violent tribal deity. However, he claims that none of the violent accounts in the Old Testament comes close to our modern Greco-Roman concept of a God who punishes people in Hell for eternity. He contrasts the violent exploits of ‘a character named God’ with the orthodox depiction of ‘a deity who tortures the greater part of humanity for ever in infinite eternal conscious torment.’ (Pg. 130)

Brian holds that the biblical revelation of God moves from a violent tribal God to a Christ-like God. As a result, he writes that ‘we cannot simply say that the highest revelation of God is given through the Bible… Rather, we can say that, for Christians, the Bible’s highest value is in revealing Jesus, who gives us the highest, deepest and most mature view of the character of the living God.’ (Pgs. 150-151) Of course, Jesus is the purest and most direct revelation of the Godhead, but we cannot lift our understanding of Jesus out of the full biblical context. Where other than in the Bible do we find an account of who Jesus is and what He said and did? Equally, how can we adequately understand what He said and did, without appreciating the Old Testament background? And, how can we fully comprehend what He said and how to apply it without the writings contained in the balance of the New Testament? The Gospels give us what Jesus said and did, the Old Testament gives us why He did and said what He did, and the New Testament writings give us how to understand and apply what Jesus said and did.

Question Four: Who is Jesus and why is He important?

I have no problem with most of what Brian says about the Lord Jesus Christ. What he doesn’t say troubles me. He doesn’t say that Jesus is divine and he doesn’t say that Jesus is Lord and is thus to be obeyed. My other problem comes with his statement, right at the end of this section of his book, that Jesus ‘did not come merely to ‘save souls from hell’. No he came to launch a new Genesis, to lead a new exodus, and to announce, embody and inaugurate a new kingdom, as Prince of Peace.’ (Pg. 180) His use of the word ‘merely’ could indicate that Brian believes that Jesus came both to save souls from hell and to initiate and model a social agenda. However, as becomes clear in his responses to the next few questions, Brian does not believe in ‘the gospel of salvation’ in its orthodox sense, nor in Hell. So, according to Brian, Jesus came as a social and not a spiritual saviour. This is a typically liberal view. Orthodox theology does not discount social transformation, but it makes it subordinate and subsequent to spiritual regeneration.

I read and reread the chapters giving Brian’s response to question four but I can’t find where he actually answers ‘who is Jesus and why is He important?’ other than in the following statement. ‘Jesus matters precisely because he provides us with a living alternative to the confining Greco-Roman narrative in which our world and our religions live, move and have their being too much of the time.’ (Pg. 168).

Question Five: What is the gospel?

Given Brian’s understanding of the overarching biblical narrative, how we should understand the Bible, the nature of God, and the mission of Jesus, his response to this question should not come as a surprise. He writes that the Gospel, ‘wasn’t simply about a new way to solve the religious problems of ontological fall and original sin… It wasn’t simply information about how individual souls could leave earth, avoid hell and ascend to heaven after death. No: it was about God’s will being done on earth as in heaven for all people. It was about God’s faithful solidarity with all humanity in our suffering, oppression and evil. It was about God’s compassion and call to be reconciled with God and with one another – before death, on earth. It was a summons to rethink everything and enter a life of retraining as disciples or learners of a new way of life, citizens of a new kingdom.’ (Pg. 186)

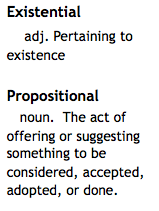

Here again Brian presents only half a truth. In his discussion on the nature of the Bible, he states that it is essentially only a medium for community and individual encounter with God. It isn’t ‘only’ this, it is also a written revelation of God’s will for humanity, the church, and us as individuals – it is both existential and propositional. In this section, Brian declares the temporal aspect of the Gospel while ignoring the eternal aspect. He ignores scriptures such as the John chapter three discourse that culminates with probably the most well-known words in all of scripture; "For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” The orthodox understanding of the Gospel is that it is the good news of eternal life in Christ Jesus. Yes, of course that new life starts here on earth and must express itself in goodness, kindness, compassion and service, but it doesn’t end at that.

Given Brian’s understanding of the overarching biblical narrative, how we should understand the Bible, the nature of God, and the mission of Jesus, his response to this question should not come as a surprise. He writes that the Gospel, ‘wasn’t simply about a new way to solve the religious problems of ontological fall and original sin… It wasn’t simply information about how individual souls could leave earth, avoid hell and ascend to heaven after death. No: it was about God’s will being done on earth as in heaven for all people. It was about God’s faithful solidarity with all humanity in our suffering, oppression and evil. It was about God’s compassion and call to be reconciled with God and with one another – before death, on earth. It was a summons to rethink everything and enter a life of retraining as disciples or learners of a new way of life, citizens of a new kingdom.’ (Pg. 186)

Here again Brian presents only half a truth. In his discussion on the nature of the Bible, he states that it is essentially only a medium for community and individual encounter with God. It isn’t ‘only’ this, it is also a written revelation of God’s will for humanity, the church, and us as individuals – it is both existential and propositional. In this section, Brian declares the temporal aspect of the Gospel while ignoring the eternal aspect. He ignores scriptures such as the John chapter three discourse that culminates with probably the most well-known words in all of scripture; "For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” The orthodox understanding of the Gospel is that it is the good news of eternal life in Christ Jesus. Yes, of course that new life starts here on earth and must express itself in goodness, kindness, compassion and service, but it doesn’t end at that.

Of course, Paul’s letter to the Roman’s presents particular problems for Brian’s earth-bound gospel but he gets around this by redefining the purpose and content of the epistle. ‘Paul never intended his epistle to be an exposition on the gospel.’ (Pg. 191) he writes.

Question Six: What do we do about the church?

If Jesus’ mission was social transformation (Kingdom of God), and the Gospel is the good news of God’s agenda of social transformation, then it makes sense that churches are ‘communities that form Christ-like people who embody and communicate, in word and deed, the good news of the kingdom of God.’ (Pg. 220) This is a very one-dimensional description of the church’s reason for existing. Prominent biblical analogies for the church include Body of Christ, Household (family) of God, and pillar and foundation of truth.

Question Seven: Can we find a way to address sexuality without fighting about it?

The bottom line we would expect from Brian here is that because most civilised cultures accept homosexuality then so should we Christians. Biblical prohibitions were set within a less tolerant culture and should not stand in our way. Actually, Brian does not clearly say this. Instead, deviating somewhat from the actual question, he asks whether ‘humans were made to fit into an absolute, unchanging institution called marriage, or whether marriage was created to help humans – perhaps including gay humans? – to live wisely and well in this world.’ (Pg. 237) Then, he likens the current gay debate to the church’s reaction to Copernicus and Galileo, and its more recent response to fossil evidence of an ancient earth and Darwin’s theory of evolution.

He then restates the Gospel as the good news of God as liberator, creator and reconciler. Finally, he presents insights into how the Ethiopian eunuch of Acts 8 must have compared Hebrew rejection with Phillip’s acceptance. His climax to this story reads, ‘As Philip and the Ethiopian disciple climb the stream bank, they represent a new humanity emerging from the water, dripping wet and full of joy, marked by a new and radical reconciliation in the kingdom of God.’ (Pg. 246) This is where he leaves the reader to deduce a suitable stance on homosexuality.

See also http://www.rpmministries.org/2010/03/responding-to-brian-mclaren%E2%80%99s-question-7-the-sex-question/

Question Eight: Can we find a better way of viewing the future?

‘There is no single fixed end point towards which we move, but rather a widening space, opening into an infinitely expanding goodness.’ (Pgs. 261-261) This of course leaves no room for a Hell of any kind, or for a second coming of Jesus. Brian explains New Testament references to the Parousia as ‘the full arrival, presence and manifestation of a new age in human history. It would mean the presence or appearance on earth of a new generation of humanity, Christ again present, embodied in a community of people who truly possess and express his Spirit, continuing his work.’ (Pg. 266) He claims that this new age started in AD 70 and his advice to us is ‘not to wait passively for something that is not present (apousia), but rather to participate passionately in something that is present (parousia).’ (Pg. 267)

So, in Brian’s grand narrative there is no Hell, and no second coming of Christ, but rather on-going eternal life for all.

See also http://www.rpmministries.org/2010/03/responding-to-brian-mclaren%E2%80%99s-question-8-the-future-question/

Question Nine: How should followers of Jesus relate to people of other religions?

‘Evangelism would cease to be a matter of saving souls…No, instead, a reborn, post-imperial evangelism would mean proclaiming the same good news of the kingdom of God that Jesus proclaimed.’ (Pg. 290) Then he writes, ‘This kind of evangelism would celebrate the good in the Christian religion and lament the bad, just as it would in every other religion, calling people to a way of life in a kingdom (or beautiful whole) that transcends and includes all religions.’ (Pg. 291) But, to be able to biblically justify this pluralistic approach Brian has to deal with, what he calls the ‘reflex verses’ that contradict his position. So, concerning John 14:6 which quotes Jesus as saying that He is the only way to the Father, Brian writes that it ‘has nothing – absolutely nothing – to say to the questions it is commonly quoted to answer.’ (Pg. 291) He claims that Jesus is simply answering the question “Jesus, where are you going?” and that if we don’t see His answer in terms of this question then we are ‘not interpreting his words: you’re misappropriating them, twisting them, abusing them.’ (Pg. 292). In order to support his contention, Brian has to reinterpret verses 1-3 where Jesus spoke about going to His Father’s house. He writes, ‘Many assume that ‘my Father’s house’ means ‘heaven’, which sets up John 14:6 to explain how to go to heaven.’ (Pg. 294) Then he points out that in John 2:15-17 the words ‘my Father’s house’ refer to the Jerusalem temple. Next, he extends the argument by pointing out that Jesus referred to His own body as the temple. A little further down the page he equates Jesus’ body with the church. So Fathers House = Temple = Jesus = Church. He then concludes his case with the claim that in John 14:6 Jesus was ‘telling them that there will be a place for them in the new people-of-God-as-temple that Jesus is preparing the way for.’ (Pg. 295) Brian then writes, ‘In this way, then, it appears clear that the term my Father’s house – like the terms life, abundant life and life of the ages – is, like Jesus’ core message of the kingdom of God, not about the afterlife but about this life.’ (Pgs. 295-296).

Of course all of this ignores verses 1 -4 with its analogy of a groom who prepares an additional wing onto his father’s home, marries his bride, and then takes her to the now extended family home. It also ignores Jesus statement that “I will come back and take you to be with me.” And it also ignores Jesus’ comparison of himself with the Father (vs. 7 - 9). Instead, we are expected to buy into a convoluted daisy chain that reinterprets the passage!

See also http://www.rpmministries.org/2010/03/responding-to-brian-mclaren%E2%80%99s-question-9-the-pluralism-question/

Question Ten: How can we translate our quest into action?

It really isn’t necessary for me to comment on this last question because I do not believe we should be translating Brian’s quest into action of the type he envisions. Quite the contrary, we should be taking stock of just how the orthodox Faith can be diluted and humanised into a liberal faith, and walk away from this as fast as possible.

Conclusion

It is good to ask questions and to seek deep and satisfying answers. It is reasonable to agonise over a Christianity that has so often presented itself as harsh, loveless, and power mad. It is evidence of a tender heart to wonder how a loving God could consign the bulk of humanity to eternal conscious torment. But, it is neither good or reasonable to attempt to recast the biblical narrative, redefine the nature of the Bible, and reformulate the principles of interpretation in order to create answers that the seeker finds acceptable. This is what I think Brian has attempted to do.

The first question concerned the overarching storyline of the Bible. The ‘new’ Meta Narrative according to Brian reads as follows. God created man good and eternal. Man has made mistakes but God has used these to evolve human potential and wholeness. There never was a fall into sin and death and so there was no need, in that sense, for Christ’s atonement on the cross of Calvary. Man never died spiritually so there is no need for a ‘new birth’ of anything other than a philosophical kind. Because there was no ‘fall’ there can be no Hell, no judgement as we understand it, and therefore no need for Jesus to come again. Our mandate, according to Brian, is not to save souls but to reform society, uplift individual lives, and accommodate God-seekers of all religions. The church exists for this purpose. The end. This is, of course, nothing like the orthodox Meta Narrative, which in turn is nothing like the Greco-Roman parody that Brian claims it is.

The second question was about how we should understand the Bible. Brian proposes that we should understand it as a cultural library and access and interpret it in terms of our current culture. He holds that its inspiration lies in how it provides us with a means of dialoguing with God within our current contexts. He does not see it as authoritative. The orthodox understanding, however, is that the Bible is both inspired and authoritative as well well as both propositional and existential.We understand it with reference to its original cultural context and we apply it in our current context.

His third question was ‘is God violent?’ and his fourth question concerned the importance of Jesus Christ. His contention is essentially that the scriptures merely record the understanding of succeeding generations who projected their own violent natures onto God. He correctly identifies the Lord Jesus Christ as the final revelation of God yet he appears to disconnect Jesus from the rest of the scriptures. The result is more a Jesus of liberal philosophy than the Jesus of the Bible.

Question five was about the nature of the Gospel. Brian’s gospel is the good news that God loves everyone and that all people are on an ever-expanding eternal journey into the realm of His love and presence. ‘Salvation in this life equates more to social transformation than just personal transformation, and the life long process of being made into the image of God.’ The orthodox understanding of the Gospel is that it is the good news that in Christ Jesus all people can have eternal life if they accept what He has done and commit to His lordship. Salvation is inclusive to all who repent and believe but exclusive in that this salvation is only available in and through Jesus Christ.

These then are the five most important questions and Brian’s responses to them. The second set of four questions concern the applications of the first five responses to issues such as the purpose of the church, sexuality, the future, and world religions. The final question is a sort of ‘where to now?’, to which I respond, ‘get back to orthodoxy…. Fast!’

For a comprehensive, very critical, but long audio of an academic panel discussion see also

http://www.sbts.edu/resources/chapel/chapel-spring-2010/panel-discussion-a-new-kind-of-christianity-brian-mclaren-recasts-the-gospel-2/